Are there students in your classes who struggle to read and understand, think critically, or stumble when expressing their ideas orally or in written formats? Do they require the same types of supports to succeed? In the Simple View of Reading (SVR), Gough and Tunmer (1986) hypothesized four types of readers and reasons for their reading success and difficulties.

|

Type 1: Typical Reader Strong decoding and language comprehension skills |

Type 2: Dyslexic Reader Weak decoding but strong language comprehension skills |

|

Type 3: Garden-Variety Poor Reader Weak decoding and language comprehension skills |

Type 4: Hyperlexic Reader Strong decoding but weak language comprehension skills |

Getting Off and On Track

Building off the SVR and Chall’s (1983) stages of literacy development, researchers Spear-Swerling and Sternberg (1996) theorized that students’ reading development can get “off track” at various stages of development and back on track with the right interventions.

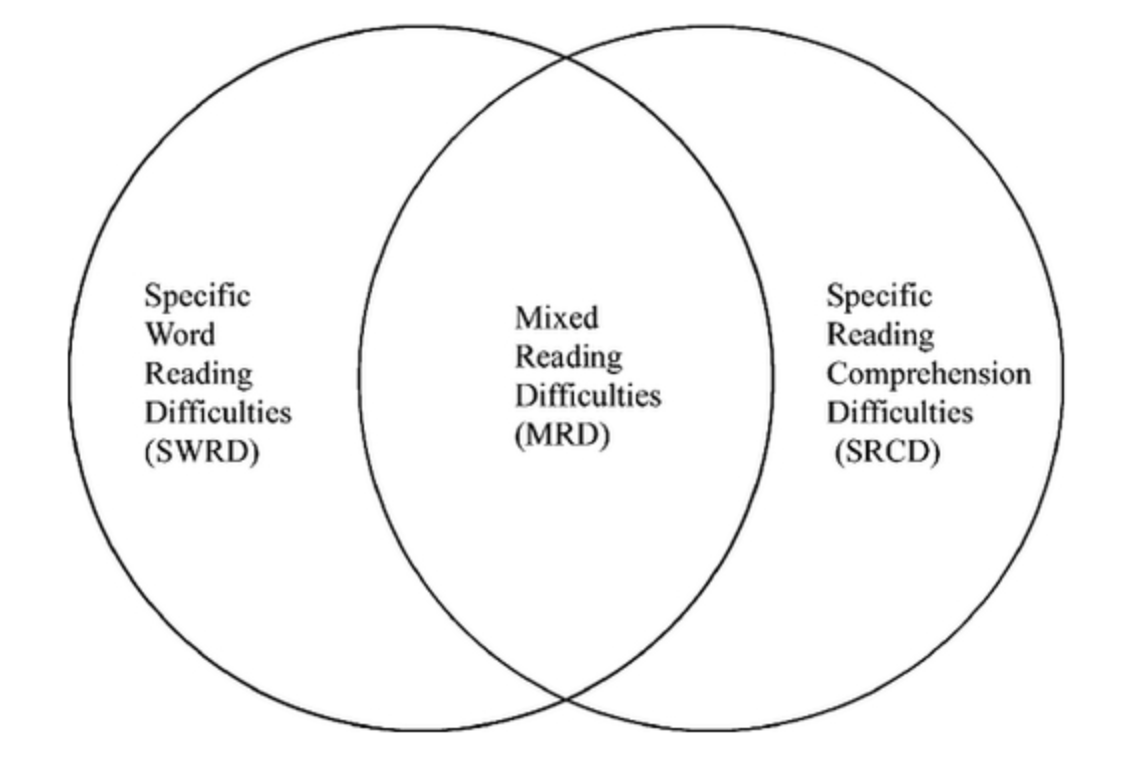

More recently, Dr. Spear-Swerling (2015) focused on three common profiles of struggling readers including those with specific word reading difficulties, specific reading comprehension difficulties, or a mix of reading difficulties (i.e. decoding and comprehension issues). Sound like any students you know?

The SVR and Spear-Swerling’s work remind us that students’ literacy development could stall for very different reasons across their academic career. Yet, the primary, and often sole, focus of reading assessments and interventions of middle and high school readers has long remained reading comprehension. Are you surprised? Remember that, historically, middle and high schools have focused on students’ “reading to learn” skills, which primarily focus on reading comprehension.

The SVR and researchers like Dr. Spear-Swerling remind us that we need to dig deeper than “students don’t understand what they are reading” and figure out why students aren’t reading and understanding. Is it a lack of vocabulary? Are they disfluent readers (e.g., slow and laborious) or disfluent decoders (e.g., having to break down too many words as they read or unable to decode unknown words)? Do they need strategies for interacting with text or simply more opportunities to apply the strategies they already know in a variety of texts? Are they just not engaged by the material? One or many of these could cause a student to experience distress when reading or writing.

Models of literacy development not only help us to understand how typical and atypical readers develop but also how we might best design instruction to meet readers’ needs. Although the research base is still emerging for adolescent literacy best practices, early successes are showing the unique importance of focusing on students’ skills development in areas such as vocabulary development and structural and morphemic analysis, as well as their will to read, which focuses on the importance of motivation and engagement, and socially engaging learning opportunities for adolescent learners (Baye, Inns, Lake, & Slavin, 2018; Scammacca, Roberts, Vaughn, & Steubing, 2010). Embedding these elements within your literacy instruction and across disciplines is doable — and essential — to developing lifelong readers, writers, and thinkers.