In which I continue my quest to find out how expert educators are viewing the new assessments their students are taking. Today, I report on Artesia High School, where students recently took the Smarter Balanced assessment for the second time. For the past three weeks, I have been writing about Artesia’s improvement. Read Artesia’s story and see how changes to school culture and instruction have helped bring about measurable improvements.

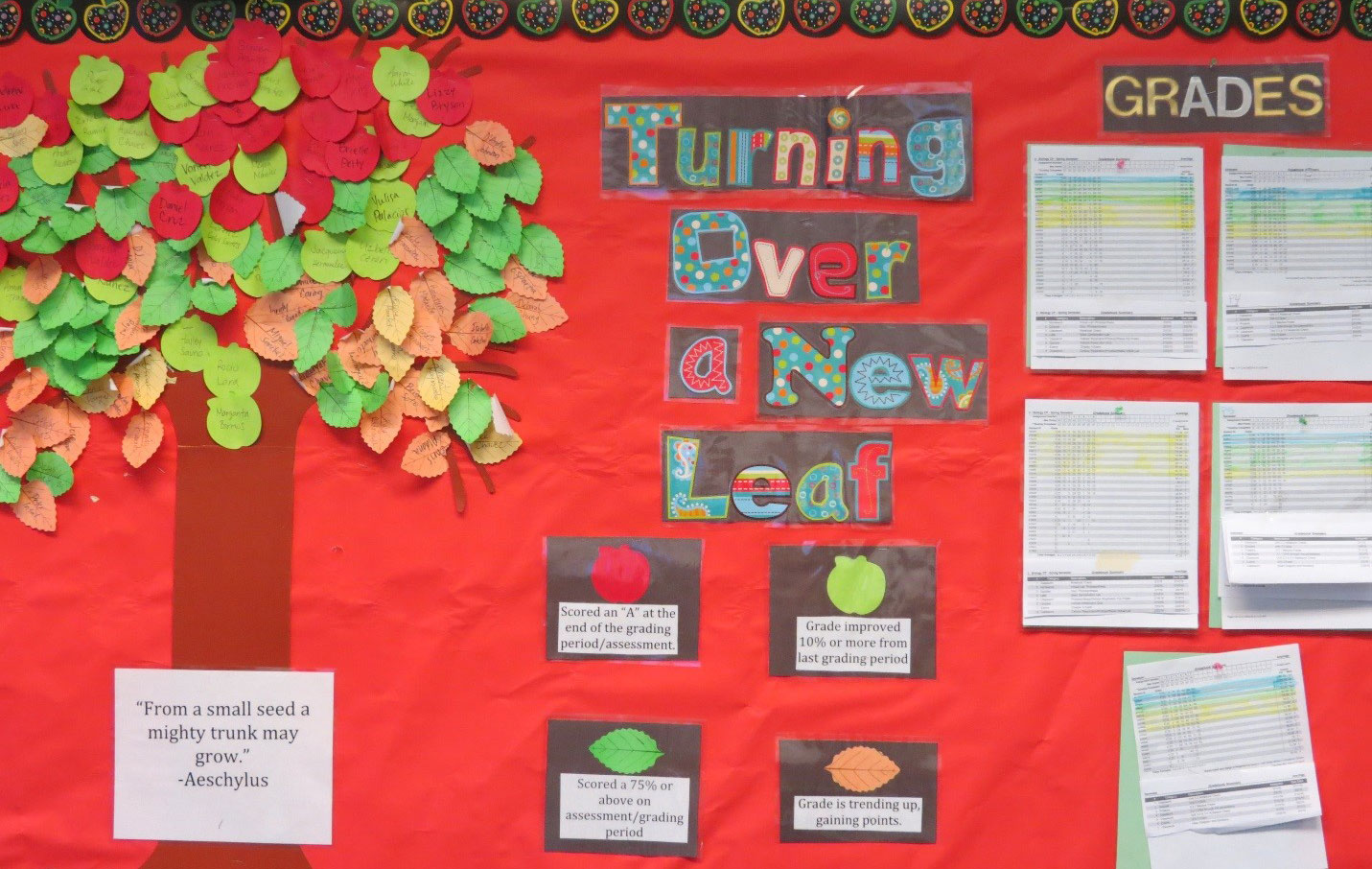

Most of Artesia’s classes have a “data wall” to celebrate high achievement and improvement.

Until last year, high school students in California took a lot of tests. They took end-of-course tests in math, reading, writing, science, and history, which measured whether they had learned what they were supposed to in these classes. Then they took culminating high school graduation tests in reading, writing, and math, which gauged whether they were ready to graduate.

Each test was an opportunity for students to see whether they were learning what they were supposed to learn — and for teachers to see how well they were teaching what students were supposed to learn.

Teachers could see that their teaching was stronger in some topics than others and — in schools where such information was shared — they could see which of their colleagues they should be learning from. That’s because they received student-by-student reports with item analyses. The old tests, in other words, provided a lot of information that was useful not just to students and their families but to teachers and their schools.

But last year, all that testing was reduced to just one state science test in 10th grade and two tests in 11th grade, one in English language arts and one in math. The 11th-grade tests were developed by Smarter Balanced, one among the “new generation” of tests, designed to see if students are mastering the knowledge and skills outlined in Common Core State Standards.

Smarter Balanced is administered to students from third through eighth grade, and then not again until their junior year of high school when, if they score at “proficient or above,” they are considered to be good candidates for credit-bearing classes in college or career and technical training. In fact, more than 200 colleges — many in California — have agreed that if students score proficient or above they will immediately be enrolled in credit-bearing classes.

To those worried about students taking too many tests, this was probably a welcome move. But for educators who used the old tests to see how they and their students were doing, and to set targets for improvement, the change has been a bit of a blow.

“It’s like flying blind,” said Sergio Garcia, principal of Artesia High School in the ABC Unified District in Los Angeles County.

Over the past 12 years, Garcia has led remarkable improvement at Artesia High School, where 75 percent of the students qualify for free and reduced-price meals, and most of the students are Hispanic. Last year, 97 percent of students graduated, with most going on to college. This year, the goal is for 100 percent of students to at least apply to college.

Key to the process of helping teachers work together to improve instruction was information from the state tests, which helped identify which students really understood the Pythagorean Theorem and which needed help; which students wrote coherent essays and which didn’t, and who their teachers were. Being able to expose and learn from expertise was important to the improvement at the school, Garcia said. “We were not shaming. We were not blaming. We were using [data] for growth.”

Smarter Balanced doesn’t report that level of detail. Right now it only reports on students’ overall scores and achievement level, which doesn’t give teachers nearly the amount of information they used to have.

Another of Garcia’s concerns is, “How do you make sure everyone is teaching what they’re supposed to be teaching?” He worries that without the kind of consistent, clear information they used to get, teachers will naturally revert back to teaching what they prefer to teach rather than teaching what students need to learn.

This is only the second year of Smarter Balanced, and Garcia hopes that as the test matures schools will receive more extensive information about how students are doing on different questions and on different topics. Also, as time goes on, schools will be able to see trends, which will provide additional information on whether what they are doing is working.

“If you look at our baseline data from last year, it’s not impressive,” Garcia said, adding that he is often told how well Artesia did because it matched the state in math and exceeded it in English language arts. “I’m not impressed.”

However, he predicted, “This year you’ll see a jump.” It will be what he calls a “logistical improvement,” because the school is adjusting many of the test-taking logistics. For example, students took both ELA and math tests on the same day last year. “They were tired. This year we’re not doing that.” Now, the right equipment is in place in the right places and students have seen practice questions, all of which will give the school a bump, Garcia thinks.

But, Garcia said, the “real results will come next year. That’s when you’ll see what we’re made of. Kids will have been taught to Common Core standards for two years, and should have the right preparation.”

But he’s still hoping for more information.